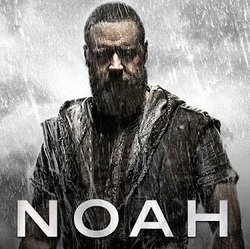

This past week, I watched the new movie Noah with considerable interest. The newest book of my Genesis commentary deals largely with the story of Noah and the moral questions raised by the Noah narrative. Naturally, whether a person writes a script or a commentary on a biblical story, Aronofsky’s film is an excellent midrashic exposition of an old familiar biblical story. The meaning of “midrash” is interpretation. Whenever we interpret a biblical narrative or law, our interpretations say more about us—the readers—than it does about the text itself. This point certainly applies to the new Noah movie that features the actor Russell Crow as Noah.

The movie seemed to borrow ideas from the Book of Enoch, which speaks about the fallen angels who came down to earth. However, contrary to Aronofsky’s portrayal that the fallen angels wanted to help humankind, God had warned the angels to keep their distance because they would lose their spiritual innocence and become more corrupt than the mortals these angels criticized. In effect, these supernatural beings caused the rapid deterioration of early man.

Like Monday morning quarterbacking, it is easy to criticize a team for failing to make the correct play of a contested football game. Hindsight is typically 20/20. According to the Book of Enoch, the Watchers found the earth girls, well—seductive. They fathered children who were the Greek equivalent of the demigods, whom Zeus and the deities of Olympus decided to wipe out through a flood! Although the Watchers wanted to improve the earth, they only made it worse. [1]

This is one example of how Aronofsky veered from the ancient Judaic literature that was written about the Flood almost 2000 years ago. Much of Aronfsky’s narrative depicted the sons of Noah as not having wives when the flood occurs. However, the biblical narrator flatly says that Noah’s sons were married before the Flood had occurred. By denying this detail, Aronfsky completely rewrites the story of Noah in a manner that is radically different and disingenuous. The movie Noah in some ways reminded me a little of Braveheart, Prophecy, Transformers, Psycho, and the “Binding of Isaac.”

One more detail, Aronofsky and Russell Crowe like showing the audience that Noah really knows how to fight! Aronofsky also portrays Noah as wearing black leather pants and jackets; not only is such an image of Noah inconsistent with the idea that he was a vegetarian, leather pants were not invented until the 8th century B.C.E., by the Persians. Aronofsky probably did not want to show a bunch of men fighting in togas or flowing robes. We can certainly forgive him for that minor inaccuracy.

Darren Aronofsky’s Noah is a postmodern reformatting of the biblical narrative we all grew to know as children. Yet, despite some of these criticisms, there is much to admire about the film.

The dramatic portrayal of Cain and Abel and its cascading images throughout recorded history was visually effective. The biblical writer of Noah probably would have shared Aronofsky’s disdain for urbanization and man’s lust for power. Some critics think Aronofsky attributes the flood to man giving up his vegetarian diet. Yet, even the rabbis suggest that the Seven Noahide Laws included a precept not to act cruelly toward animals—which was most likely a reaction to the antediluvian behavior of that generation.

The psychological transformation of Aronofsky’s Noah is remarkable. According to the biblical story, God became fed up with humankind and its penchant for violence. This thought is not expressly evident in the movie for God never really “speaks” to Noah, but communicates to him through dream imagery and visions.[2]

Aronofsky portrays Noah as a man who hated humanity because of their wickedness. This would explain why he refuses to aid Ham’s girlfriend because of his contempt for humanity. Yet, he is prepared to sacrifice his daughter-in-law, and her two baby girls who miraculously are born forty days after the flood subsides! (Now that’s a real miracle!) After the flood, Noah comes to a strange realization that God does not want the world to have human beings because of their violent ways. Yes, Aronofsky’s Noah sounds more like the Christian theologian Augustine who believed that man is incurably evil and is incapable of redeeming himself. Interestingly enough, Aronofsky demonstrates why Noah did not ask God to save humankind. The reason is simple: he despises what human beings have become! This interpretation is certainly consistent with the rabbinical view that criticizes Noah for his lack of human concern for his fellow beings.

When Noah came out of the ark, he opened his eyes and saw the whole world completely destroyed. He began crying for the world and said: “Master of the Universe! You are called Compassionate, but You have shown compassion for Your Creation?” The Holy Blessed One be He replied, “Foolish shepherd! . . . I lingered with you and spoke to you at length so that you would ask for mercy for the world! But, as soon as you heard that you would be safe in the ark, the evil of the world did not touch your heart. You built the ark and saved yourself. Now that the world has been destroyed, you dare open your mouth to utter questions and pleas?! [3]

This part of the film seemed as though Aronofsky had recreated the Binding of Isaac and it is only the humanity of his wife who shows him the error of his ways. Despite himself, Noah eventually comes to see that God desires that we as humans redeem and save the world around us.

Does this have ecological relevance for today? Of course it does. Christian evangelicals ought to embrace this aspect of the Noah story. Regardless whatever one may feel about Aronofsky’s Noah, the writer succeeded in portraying Noah as an ecological hero, for indeed, he is—he single-handedly saves the world and himself as well.

If God could choose an imperfect person like Noah to make a difference in bettering and improving the world, then there may be hope for the rest of us who are reading his story. Noah is an entertaining film; despite my reservations on some of the details of the film, I will give it 4 stars!

======

Notes:

[1] In Book 1 of Metamorphoses, the Roman poet Ovid (43 B.C.E. – 17. C.E.) weaves an elaborate chain of tales pertaining to the creaturely and cosmic transformations. Like the thematic layout of Genesis, Ovid first begins his work narrating about the creation of the world, Ovid then transitions to how the council of gods decided to bring a great flood to destroy all life. There is a clear etiological purpose of both the biblical and the Metamorphoses narratives in defining how the present world has become what it is. In addition, both books contain numerous moral parables about the human condition. Ovid’s retelling of the Flood story differs in one very important respect from the Mesopotamian narratives. Like the Noah narrative, Ovid attributes the flood not to the gods’ caprice or insomnia, but to human corruption and evil.

[2] Parenthetically I must add that Maimonides probably would have enjoyed this part of the film for he always maintained that God speaks to human beings through dream or visionary imagery.

[3] Zohar Hadash Noah, 29a

*

RabbiMichael Leo Samuel is spiritual leader of Temple Beth Shalom in Chula Vista. He may be contacted via [email protected]

San Diego Jewish World seeks sponsorships to be placed, as this notice is, just below articles that appear on our site. To inquire, call editor Donald H. Harrison at (619) 265-0808 or contact him via[email protected]

RSS Feed

RSS Feed